Integrated Delivery

Insights 08.06.2025

The Weekly Podcast with Rachel Horgan

Tess Wakasugi-Don

Principal

We can probably all agree that deconstructing a 100-year old building and putting it back together again piece by piece is a daunting task. Now imagine reconstructing that building 60 feet north of its original location, integrating it with a new structure with strict vibration limitations, restoring its original representation prior to years of modifications, and bringing it up to current building code—all while preventing damage to 2,760 pieces of original terra-cotta.

This is the story of how we reimagined preserving a piece of Seattle history, and used advanced technology tools and the collaborative brain power of architect, historical preservationist, and builder to breathe new life into it.

Ford and Pacific McKay buildings at the Allen Institute.

When Vulcan nominated the Ford McKay and Pacific McKay buildings for landmark status in 2006, they were protecting a significant piece of Seattle’s automotive history. Unbeknownst to many passersby, William Osborne McKay’s automobile shop and glamorous terra-cotta-clad showroom were the impetus for Seattle’s thriving auto row that, by 1939, boasted over 40 automobile-related businesses within a 12 block radius. As Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood undergoes its next transformation into a thriving center for high tech business and groundbreaking research, it is fitting that these two long-neglected buildings are recognized for their role in the area’s first boom time.

After years of multiple ownerships, modifications and lots of wear and tear, these two buildings weren’t much to look at, going unnoticed—despite the fact that they sat in the midst of one of Seattle’s busiest streets. If Vulcan had not sought official landmark protection from the City, they would have met a very different fate in the 2009 Mercer Corridor reconfiguration.

Instead, in 2008, Vulcan promised to deconstruct the buildings piece by piece and place them into storage for safekeeping. Seven years later on June 10, 2015 when the buildings were all but forgotten, the massive tarp shrouding Vulcan’s newest construction site dropped, revealing a blast from the past. It was so sparkling clean you almost expected to see Mr. McKay pull up in his shiny new 1922 Ford.

The flawless incorporation of the two 1900-era landmarks into the modern, futuristic Allen Institute is the result of skill and hard work. There was much more than meets the eye to this intricate, mind-bending process.

The hope of seeing the two landmark buildings standing again in their original form mandated experts in multiple trades and niches.

Enter: BOLA. With a passion for history and preservation, this boutique architecture firm specializes in the restoration and rehabilitation of historic structures. BOLA, in turn, entrusted the work of dismantling the elaborate terra-cotta to Pioneer Masonry, whose team cleaned and catalogued each piece, refurbishing the most damaged along the way. They took a staggering 5000 photos of the tiles to properly catalogue both buildings.

The job of documenting the extensive interior molding and plaster went to PCS, who also made molds of pieces determined unsalvageable.

After just four months, with eight binders of specs, thousands of photos, granite, a fountain, stairwells, wood trim, an arched entry transom, window frames, and 116 crates filled with 2,760 pieces of terra-cotta tucked away safely in a warehouse down the street, the team walked away from a job well done. Or so they thought …

Six years later, Vulcan announced plans to build the new Allen Institute headquarters and incorporate the two historic buildings into the seven-story lab and office facility. GLY jumped on board, immediately seeking the best partners to take on the daunting task ahead. After all, taking it down was just half the battle; putting it back up—especially without the essential knowledge gained by those involved in the deconstruction—was a challenge the team embraced.

Labeled terra-cotta prior to deconstruction.

Deconstructed terra cotta.

Cleaning, cataloguing, crating the terra-cotta.

Pouring rubber mold of original interior plaster detailing.

Original woodwork for Pacific McKay crated in storage.

GLY dug into the crates to see what we were working with—reviewing all documentation, photos, scans from historic prints, etc. The process was much like laying all the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle face-up after dumping it on the table. But no amount of sifting and sorting could replace the knowledge that BOLA and Pioneer Masonry had. Without hesitation, Perkins + Will [the Allen Institute Architect] brought BOLA back into the picture and GLY welcomed Pioneer Masonry with open arms.

After several meetings and discovery sessions, with each individual taking a vested look at all the bits and pieces, the team identified the key knowns, tools, and must-haves for the project and structured them into a workable plan:

Scope of work. At the end of the day, there were five main scopes of work: Terra-cotta, Woodwork, Plaster, New Terrazzo and the New Structure.

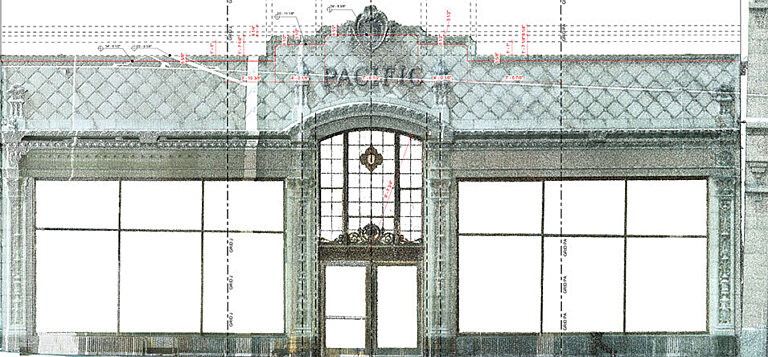

Point Cloud + 3D Imagery. Prior to deconstruction, Vulcan took a laser-based point cloud scan of the buildings. A piece of survey equipment similar to a total station sits in a fixed position, sends out a laser array, and documents a coordinate where the laser hits something. Millions of these coordinates, which contain color [RGB – red, green, blue properties], make up a cloud. The resulting 3D colored graphic creates and defines volumes of space and is almost photographic in nature.

This laser scan was one of VERY few pieces of evidence available to the team, but without a way of back-checking the laser scan against a physical building, they had no way of knowing how accurate it would be. It could be as much a hindrance as a helpful tool.

As-builts. In addition to Vulcan’s building scans, we had historic drawings of the original design and coursing. Pioneer Masonry also had their own dimension plan of the coursing.

Establishing a level of respect for history and the restoration process. It takes a lot to put something back together from nearly 100 years ago. It takes a whole lot more to put it back together based on today’s standards and codes while maintaining the integrity of the original buildings’ appearances. The team had an unspoken understanding that this wasn’t a project open to design modifications. We could restore and/or replicate, but changes to the buildings to simplify the process were out of the question.

Pioneer Masonry's color coded + numbered maps.

Section of Vulcan's point cloud.

ensuring a perfect fit: coordinating the structure.

Next, the team needed to determine how to rebuild the structure. They faced several unique challenges and road blocks. Namely a no-tolerance scenario. Once it started to go back up, there was no we-can-fix-this cushion if faced with an uh-oh moment.

For example, the facade required a new concrete backer [wall] for the terra-cotta; but how could we ensure a perfect size to fit all 2,670 pieces? There was no room for error.

The team could mock up every piece of terra-cotta and lay them out along the city block. However, this was about as unrealistic as it sounds.

Instead, in a total hands-on process taking the integrated approach of working together as the designer, builder, and more, the team fused modern technologies with old world craftsmanship.

With measurements defined and details fleshed out, it was finally time to BUILD. But still, the preservation had to tie in with the new structure for the Allen Institute from the back, top and north side of the Ford McKay Building, requiring one final plan of attack.

Layout coordinates from Revit. Using the laser scan point cloud and details the team collected, Trevor created a final 3D model that dimensioned and laid out the new building’s geometry and location prior to any physical construction—ensuring accurate installation. This process puts the pieces back together in a virtual world to confirm that old works with new. The GLY survey crew transferred the points from this model onto the site.

Energy efficiency + new code compliance. The team selected energy-efficient windows and doors to match the historic style, and used modern liquid air barriers and aerogel insulations to create an energy efficient façade that worked within the historic building profile.

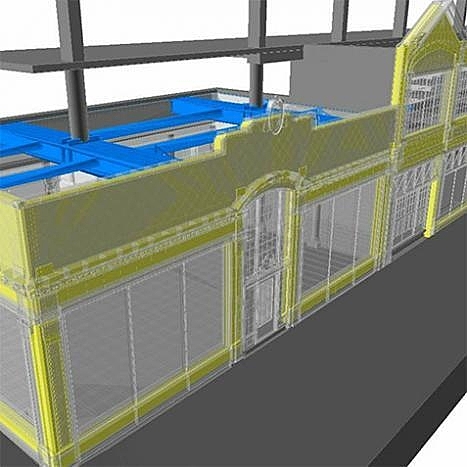

Prevent vibration. In the original design, the Allen Institute cantilevered over the Pacific McKay Building. However, while a hovering Allen Institute was visually appealing, this concept unfortunately caused vibration – potentially disturbing sensitive facility operations. Instead, the weight of the Allen Institute had to bear down and transfer through the historic landmark. The team faced a new challenge: how will the Pacific McKay structurally support all that weight above it? The go-to solution of placing a column through the middle of the Pacific McKay defeats the goal of a true historic preservation. Instead, GLY and CPL designed a steel girder support system. At two locations within fractions of an inch above the building’s ceiling, multiple girders fused together and transferred the weight of the Allen Institute [depicted in the 3D model above].

All of this was easier said than done. The team also had to ensure the concrete backer for the facade was strong enough to support all of that steel which is why [although blind to the naked eye] a precise concrete mixture AND steel bracing in the walls replaces the original building’s simple brick and mortar.

Build. GLY and specialty subcontractors got to work physically piecing the two landmarks back together. PCI installed 966 individually cast decorative plaster elements inside the Pacific McKay showroom. Pioneer Masonry reinstalled 2,760 individual pieces of terra-cotta facade and exterior granite bases. All New Glass installed period-appropriate steel and metal clad windows. Legacy Renovation refinished the historic wood. North American Terrazzo installed new terrazzo flooring to replicate the original design.

Today, the reborn Pacific McKay Building is true to its original form, inside and out. While the Ford McKay exterior is also a true representation, the interior is repurposed into gallery space. The original auto garage [at right] was a simple two-level empty shell. It was important to Vulcan to use it as a space that invited the public in. What better way than to offer free admission to Pivot Art + Culture, a one-of-a-kind art gallery?

3D model showing steel girder supports [blue].

Reconstructing Pacific McKay ceiling.

Throughout the building process, PCI and GLY re-catalogued every tiny piece and detail, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant. The only thing certain in life is change. After painstakingly preserving this little piece of Seattle’s history we want to make it as easy as possible for future generations to carry it along with them on the tide of progress.

Whether for simple repairs or in the wake of a major event such as our long-anticipated big one, this meticulously documented information will be available to help the next team protect a cherished landmark. For better or for worse the next chapter in the McKay Buildings’ story will be guided by a highly detailed, high-tech roadmap.

Then [1937]

Now [2015]

THE TEAM. Project Developer: Vulcan Real Estate; Construction: GLY; Allen Institute | Architect: Perkins+Will; Preservation Architects + Historic Consultants: BOLA Architecture + Planning; Terra Cotta Facade Restoration: Pioneer Masonry; Glass Subcontractor: All New Glass; Plaster Work: Performance Contracting; Historic Wood Refinishing: Legacy Renovation; Terrazzo Flooring: North American Terrazzo.

Director of Virtual Design+Construction

Associate DBIA™

Trevor is an industry innovator with over 22 years of experience devoted to creating synergy between architectural design and technical construction. Trevor leads strategic business planning for the company’s Virtual Design and Construction [VDC] and technology efforts and provides companywide training on GLY delivery philosophy and VDC process. Having been both a project architect and a construction manager, he identifies valuable opportunities for coordination and collaboration amongst designers, engineers, and tradespeople. Trevor respects each discipline’s individual process and expertise while ensuring constructability. Trevor’s downtime is spent playing with his kids or fishing.